The implementation of supranational regulations at the national level often provides national authorities with substantial room to engage in discretion and forbearance. Do national authorities assist banks to pass stricter supranational bank regulation? In a recent SAFE Working Paper, I study the response of national authorities to a sudden and substantial increase in capital requirements, imposed by the European Banking Authority in 2011.

To measure national discretion, I focus on regulatory bank capital. Regulatory bank capital (which differs from book equity) provides an ideal testing ground to study the intricate interplay between supranational rules and national policies. The rules governing the definition of regulatory bank capital include a plethora of deductions and instruments and provide considerable leeway to manipulate capital ratios. National authorities may assist banks' efforts to “inflate” their regulatory capital by exercising regulatory forbearance, such as by enacting favorable regulations or by making certain capital instruments eligible for regulatory capital. My main measure of capital inflation is the ratio of regulatory capital relative to book equity, capturing the amount of regulatory capital a bank reports per euro of book equity. An increase in this ratio suggests that regulatory capital increased without a commensurate increase in book equity capital.

Banks rely on discretion in the calculation of regulatory capital

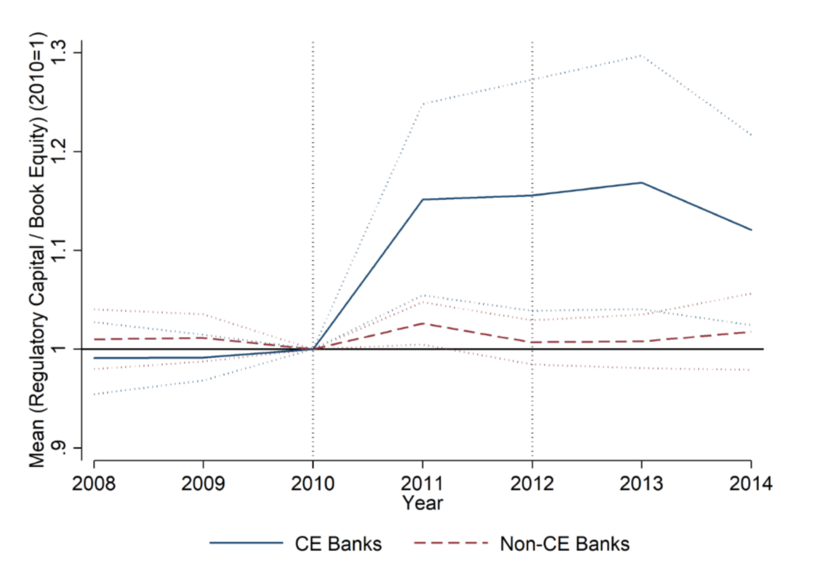

The capital exercise raised the minimum required core tier 1 (CT1) capital ratio from five percent to nine percent for a subset of European banks, while leaving requirements unchanged for other European banks. For our baseline analysis, we compare changes in the ratio of regulatory capital relative to book equity between banks subject to the 2011 capital exercise and banks not subject to the exercise. Figure 1 shows the evolution of this ratio relative to 2010 for capital exercise banks and non-capital exercise banks. Prior to the capital exercise, the ratio of regulatory capital to book equity was stable for both groups of banks. From 2010 to 2012, however, banks in the capital exercise significantly increased their levels of regulatory capital relative to book equity, implying a substantial reduction in capital deductions around the EBA capital exercise. In contrast, the ratio remained unchanged for non-capital exercise banks in the control group. Consistent with weakly capitalized banks having a stronger incentive to engage in capital inflation to pass the EBA capital exercise, these results are driven by banks with ex-ante lower capital ratios.

Figure: The ratio of regulatory capital to book equity over time

The paper shows that banks rely on discretion in the calculation of regulatory capital to inflate their capital ratios without a commensurate increase in their levels of book equity. This discretion is provided to them by their own national regulatory authorities. National authorities may assist banks' efforts to inflate their regulatory capital by exercising regulatory forbearance, such as by enacting favorable regulations or by making certain capital instruments eligible for regulatory capital. Therefore, national discretion may effectively undermine well-intended supranational rules in practice.

Simple rules and further harmonization reduce to scope of national discretion

After the initial formation of a supranational regulatory regime, a substantial tightening of the rules might trigger a heterogenous response of national authorities. To address this concern, one of the main objectives of the EU Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) is to harmonize supervisory practices. Although significant progress has been made, national authorities will continue to have substantial room for national discretion in other policy areas, such as their national tax or bankruptcy code. Policymakers should therefore be aware that potential agency problems between supranational and national authorities could undermine the effectiveness of supranational regulation. Specifically, complex regulations, such as the rules governing the composition of bank capital, are susceptible to discretion of national authorities. An important implication for the design of new supranational regulation is to give preference to simple rules over complex regulation.

Thomas Mosk is postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Banking and Finance at the University of Zurich.

Blog entries represent the personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of SAFE or its staff.